- Home

- M. F. W. Curran

The Hoard of Mhorrer Page 4

The Hoard of Mhorrer Read online

Page 4

‘Have they abandoned us down here?’ Jericho asked.

William stood silently, staring up to the hole in the ceiling. What would it take for their hosts to answer him? Could they risk trying to climb out?

The sound of footsteps rang down a flight of stairs nearby. Many footsteps. The Papal seal he wore seemed precarious now. William began to doubt they would listen. Would they believe him? After all, how many Papal delegates run around decapitating the local citizens?

‘Marresca . . .’ William said under his breath, hearing them come. ‘Be ready.’

‘What about the Papal seal?’ Peruzo whispered.

‘I’ve decided not to use it,’ William said desperately.

‘We’re fighting our way out?’ Jericho said, his voice shaking.

‘If we have to,’ William replied. ‘Ready, Marresca?’

‘Ready,’ The young monk replied quietly.

‘Only on my signal,’ William urged him, ‘not before. And try not to kill anyone.’ He knew Marresca’s skills. The blond monk could break a man’s neck with his bare hands and could disarm several men before any drew breath. Marresca would be their one chance of escaping, if it came down to it.

From the direction of the footsteps appeared a light, a gentle glow that grew and grew. When it emerged from the flight of stairs at the far side of the cells, it was joined by voices, some low, some excited.

William stepped back from the bars and joined Marresca in the shadows as men approached.

‘Can you stand, Peruzo?’ William whispered.

Peruzo pulled himself up from the floor with a series of groans. ‘Barely . . .’ he said.

The voices were now at the cells, led by one gaoler holding a brand that lit up both chambers, stinging William’s eyes with its bright fiery glare.

There came a flurry of excited words again, as if an argument had begun between two of their hosts.

‘What are they saying?’ William asked.

Peruzo listened but did not reply. The men were not only speaking in German, but another language the lieutenant did not understand.

With a series of muddied movements, one of the gaolers unlocked Peruzo and Jericho’s cell.

‘Stand by me, Marresca,’ William murmured and heard the young lieutenant step forward shoulder to shoulder. ‘Peruzo, what are they saying?’

‘They’re apologizing I think,’ he said gleefully.

‘They’re what?’

One of the men came into the cells, a man William found familiar. It was the same man they had seen in the tavern. The contact who had gestured to the stairs at the inn; the lawman. He began shouting at the gaolers, one scurrying away while the other stood dumbstruck in the doorway, the torchlight flickering shadows about them.

‘He apologizes for our treatment, Captain,’ Peruzo translated. ‘If he’d known earlier, he would have ordered our release.’

‘Well, a late apology is better than none at all,’ Jericho said gladly.

With a click and banging of chains on metal, William’s cell was opened and they were led out by a wary gaoler who kept his distance from him. Peruzo, supported by Jericho, was already in the corridor with the sorry-looking official who kept apologizing before abusing the gaolers some more.

‘Peruzo, tell them I demand to see Brother Anthony,’ William said wearily. But he knew in his gut that the brother’s fate would be worse than theirs.

III

The outside air was pungent with the odour of smoke and drizzle, the musty smell that marked so many cities across the Continent. For William, it brought memories of London when he was just a boy when tall chimneys of factories had only just started growing from the city’s skyline, gushing great clouds of rolling grey across the sky.

The faint drizzle dampened their clothes, their hair and their skin; an insidious downpour they could see but barely feel until water dripped over their brows and down their cheeks. When they eventually crossed the river, the drizzle had ceased and all that lingered was a sweet spring aroma mixed with the industrial tang of burning wood and coal.

William’s mood had barely lightened since their release from prison. At his request, they had been led to Brother Anthony finding the monk half naked and cold on a butcher’s slab in the gaol mortuary, his eyes staring out blankly into whatever realm his soul had been sent to. He had evidently been neglected.

William was furious and he delivered his demands abruptly and without negotiation: the gaolers were to wrap Brother Anthony’s body in a shroud and return the Scarimadaen to them immediately. A cart would be provided at the sheriff’s expense to take Brother Anthony away, returning also their weapons and their horses.

On their part, the gaolers wanted William and his men out of the gaol as soon as possible. They were still convinced these strangers were warlocks or sorcerers of some kind, and their presence was unsettling. The official who had served as Peruzo’s contact and now as their liberator ensured that all demands were met, in repayment for the retribution William and his men had dealt out on those responsible for killing one of his militia. As long as they promised to leave Prague immediately, all parties would be satisfied.

Within an hour, everything was prepared and William led them away to their only safe haven in the city.

The chapel in Stare Mesto was older than much of Prague, and smaller than most of the buildings surrounding it, so small that it was barely noticeable, with only its ivy-covered façade to show that it existed at all. But its parishioners knew it, as did the four figures now arriving at its doors, appearing like outcasts or beggars in their dishevelled state, each man’s clothes either grubby or torn. But it was the cart on the road with the bound body laid upon it that people marked as they strolled past on that Sunday afternoon. Curiosity was pricked to wonder who lay within the white linen, some loitering to gossip in that strange mix of German and something else.

William might have spoken, but he was too exhausted and could only rap his knuckles on the thick wood of the chapel door several times impatiently. When he met with no reply, each rap grew more frustrated and insistent. He wanted to get inside, out of the melancholy cold, to put his fallen man in the shelter of the chapel.

Eventually the door was pushed ajar.

‘Father Gessille?’ William barked.

The door opened wider. ‘Captain,’ the man greeted. ‘You have come back so late . . . What has happened?’

William pushed past him. He was beyond courtesy; the city’s charm had worn as thin as his patience. Father Gessille looked to the other three men: Peruzo hobbling inside supported by Jericho, Marresca following after, calm as ever. Then the Father’s eyes fell on the cart.

‘Who is that?’ he asked.

‘Brother Anthony,’ William replied, cupping his hands in the font. He lifted them to his lips and drank. It was an ungodly thing to do, but he was thirsty and he thought God owe d him. Shaking the drops from his hands, he marched back to the Father’s side. ‘I need help carrying him.’

‘Of course,’ Father Gessille replied.

They walked out through the slowly growing crowd of folk around the cart and Father Gessille climbed into the back and began to drag the linen-wrapped body across the boards to where William stood at the rear. William took hold of the ankles and pulled Brother Anthony along, before letting the weight of the body fall on his arms and shoulders.

The Father climbed out of the cart and took part of the weight as they stumbled back to the chapel, the shrouded body carried between them.

When they entered, Brother Jericho closed the door firmly behind them and William lowered the body onto a bank of pews, breathing hard and heavy as the burden was lifted.

‘May I see?’ Father Gessille asked.

‘Please,’ William offered, ‘after all, you will be reading his prayers at the burial.’

‘Burial?’ Father Gessille looked up. ‘Here?’

‘We should take him back home, Captain,’ Jericho said, ‘to be buried at Villeda.�

��

‘There’s no time,’ Lieutenant Peruzo said behind them. He sat drooping and exhausted on some benches a couple of rows in front of Brother Anthony’s body. ‘The body will rot before we can return.’

Jericho frowned and looked back at his captain, who agreed. ‘He will be buried here, Jericho. With all the dignity we can muster.’

‘When do you wish this?’ Father Gessille asked as he began to unravel the shroud.

‘Tonight. We leave at first light in the morning,’ William said, stretching wearily. Head bowed, he trudged down the rank of pews and out of a side entrance to where they were lodged.

IV

William ate his broth in silence. He could not sleep while the others dozed, and Peruzo snored like a drunkard or an old man. Peruzo was ageing, and the wound had brought his frailties to the fore. William trusted his experience and his skill with a sword, but there were only a few more years left in Peruzo. The War had taken its toll on him, as it had on them all.

William finished the broth and took a mouthful of wine. It was thick and oily, but slid down his throat, taking the tang of the broth with it. The food was as bad as the drink, but he had barely eaten in two days and was famished. Throughout the repast, he watched Father Gessille as he redressed Peruzo’s wound and made arrangements for Brother Anthony’s burial.

Finally, as the sun was setting, the priest came up to William. Father Gessille looked down at him hesitantly.

‘Something troubling you, Father?’

‘I examined Brother Anthony’s wounds. There was a mark upon his body. A burn mark. Did the militia do that to him?’

‘No,’ William replied abruptly, not wishing to engage in conversation about Anthony’s death.

‘Then what?’

‘Do you really wish to know Father? Many men who have succumbed to curiosity about our ways have wished they hadn’t.

‘Had these same men seen similar violations?’

‘Some had seen worse.’

Father Gessille looked appalled. He shook his head in despair and took several steps away, as though William was a danger. A threat to the flesh and the soul. ‘I would have said such marks came from torture or . . .’

‘. . . Or they were diabolical?’

Father Gessille stared at William and nodded slowly, understanding him better. ‘Then it is true. You are the ones they speak about. The hunters of the Infernal.’

William nodded, satisfied that word of their heroics had reached even this corner of the Continent. ‘We are they.’

‘And your prey was diabolical?’

‘It was. We tracked it down to a tavern just over the river.’

Gessille looked over his shoulder to the shrouded corpse with an expression of sorrow. ‘Was your discovery worth his death?’ the priest asked.

‘Just Brother Anthony’s?’ William considered this for a moment. ‘Had it cost just one life for every Scarimadaen, we would have finished this War years ago. I lost eight men in Vienna, Father. Eight. Even before we came here.’

‘Then I hope your mission has been a success,’ Father Gessille said, bewildered as he walked away, ‘for there is no drive to compel me to sacrifice so many.’

William got to his feet, staring at Father Gessille with rebuke. ‘Are you questioning my motives, Father?’ he called after him, stopping the priest in mid-step.

‘No,’ Father Gessille called back, the word echoing in the confines of the chapel. ‘But think, my son. Should a man who professes to serve the Church be so ready to make such desperate sacrifices? Does such a man truly understand his own reasons to serve?’

‘This is a war, Father. I am a soldier. My reasons are only to serve, and are grounded in honour.’

‘There is no honour in war, my son. None at all.’

William wanted to protest, but his readiness to argue had waned. ‘An exile has little choice, Father,’ he said finally as he pulled a pipe from his jacket and began packing it with tobacco. He reached to take a light from a nearby candle, putting it to the weed in his pipe.

The pipe had been a gift from a man he often thought of on cold nights such as these, a lieutenant of the Order who had been killed during William’s first mission several years ago. That man – his name was Cazotte – had started out as William’s antagonist, but they had ended their time together as friends. A friendship that was cut short by a bloody battle.

William pulled the chapel door ajar and slipped outside. Wrapping his jacket about him, he stood on the top step in the shadows of the ivy and listened to the quiet of the night as he smoked the pipe.

Lieutenant Cazotte had survived many of the rigours of William’s first mission, escaping death a number of times, saving William’s life on more than one occasion, before the final battle in the mountains of Aosta. William had not seen the lieutenant fall, but heard from first-hand accounts that it had been a ‘good death’ – if there was such a thing. A hero’s death.

But heroic deaths seemed not to matter when there was no one to talk to, or share a joke with on cold nights while you stood in the dark and smoked pipe-weed.

Above him the sky was clear, with a crescent moon high above and many stars. There were no clouds, yet there came a rumble in the air, like thunder. Perhaps it was a cannonade being practised far away on a drill field. Maybe it was a storm, lying too far from sight but loud enough to hear.

A gentle breeze suddenly caressed his skin. It quickly grew stronger, lifting William’s unruly hair. At the other end of the street he saw several men and women fleeing towards the church. One woman was in tears, while another simply turned in horror and pointed skyward, mouthing something that could have been a prayer. William followed her wavering hand and saw the sky suddenly swamped by oily clouds that rolled in fast to smother stars and moon.

Squinting against the gale that now swept by him, he put a hand over his brow and watched as lightning crackled violently across the burgeoning underbellies of the clouds. There was a blinding flash, and for a heartbeat a streak of light seared William’s sight, as it crashed down behind a row of houses in the distance. A second strike hit the same spot and William was dumbstruck. Dumbstruck that the night could be so quickly overturned, so changed by a storm that had appeared in moments . . .

But more astounded by the memory the pyrotechnics had awoken in him. A memory of seven years ago when lightning struck the frigate Iberian, which was under attack from their enemies. That strike of lightning had saved their skins that night. A night of vampyres.

A night of angels.

‘Can it be . . .?’ William murmured to himself. He grew eager, half stumbling down the steps in his haste.

The battle on the Iberian was the first time he had seen an angel ride the lightning. The last time was when his closest friend, a brother in every respect save blood, was taken by them. That he hadn’t seen Kieran Harte in so many years was reason enough to be overjoyed; that he should bring these holy terrors with him – the Dar’uka – was a greater reason to temper that enthusiasm with trepidation.

William felt his mouth grow dry with anticipation. At the end of the street, the shadows seemed to fracture. Where they should have been long and thin, they jumped and flickered as two figures emerged. In the middle distance, dogs cowered and whined, afraid of the night’s new guests.

William froze, elated yet anxious as he watched them march down the road towards him. The figures shimmered with a sapphire light that crackled about their feet and arms. As they grew closer, the light curled about their faces and hair. It was the same light that snaked about daemons as they were summoned, or across the eyes of vampyres and their wounds. But the two who approached him were not of Hell, but fought on the side of some other cause.

For these were Dar’uka. The Plainsmen. To everyone else, they were simply angels, seraphim incarnate, but beyond visions of winged babes and angelic presentations.

Despite his brave countenance, they disturbed William. Feeling clumsy, like a child, and thoroughly

humbled, he frantically tapped the pipe clear against the side of his hand as they approached. The first was a tall albino with long hair and dressed in a wolfskin cloak. A two-handed broadsword showed beneath the gown of fur and flickered with that same ethereal light, trembling up and down its edge.

The second figure had short black hair. He was shorter than the albino, but he too had a large broadsword that hung at his hip under a long black coat. While the albino was dressed like a barbarian of old, the second man was dressed in more modern attire; he might have even passed for normal in polite society.

William did not know this first man. The second, however, was familiar.

‘After all these years!’ William gasped. He began to grin, his heart pounding harder. He was suddenly overcome with joy and stepped forward to embrace the second man. ‘Kieran! I knew you would return!’ but as William approached, he faltered and his smile dropped. The Kieran Harte William once knew had changed. His face was white and gaunt, his skin the colour of ivory. The entire surface of his eyes was black, and within them flickered a smaller version of the storm that swirled overhead, lightning spilling over the lids, like tears of light sparkling down his cheeks. His hands were scarred, ruined with symbols and lines that were incomprehensible to William. And these scars flickered with that azure light, sometimes seeping from the grooves across finger and thumb, rasping the air with bright tendrils that quickly melted into oblivion only to rise again a moment later.

‘My God, Kieran,’ William murmured as he watched the lightning dance over him, ‘what have they done to you?’

‘We have come for Marresca,’ the albino said, and as soon as he opened his mouth, the words drowned William, flooding his ears with a cacophony of fractured voices that parted before him, and then merged again discordantly inside his skull.

William retreated, not even understanding what had been uttered. ‘I don’t understand,’ he groaned, wincing against the sensation.

Kieran stepped forward. ‘We have come for Marresca, William Saxon.’

William stared at his friend. A man he had known all his life. Yet this man was not Kieran. This man was not the one who had left him seven years ago. The Kieran he knew would never have been so bold and discourteous.

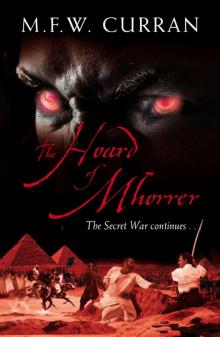

The Hoard of Mhorrer

The Hoard of Mhorrer